Book title: Nudge

Book title: Nudge

Author: Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein

ISBN-10: 0141040017

ISBN-13: 978-0141040011

Buy on Amazon.in | Amazon.com

Nudge is a book written by American behavioural economist and nobel prize (Economics) winner Richard Thaler and lawyer Cass Sunstein, who takes deep interest in behavioural economics and ethics in law-making and government policies.

The premise of the book is that one can highly influences choices and decisions that people make by subtly modifying the way that choices are presented. In doing so, they describe a role named ‘choice architect’, whose responsibility is to carefully design choices so that choice-makers can be protected from bad choices and led to good choices.

Intro

To start with, the authors dejargonise certain terms that they use throughout the book.

Econ: is a mythical homo-sapien like create whom the authors claim to be rational, calculative and immune to manipulation or emotions. In this book, they frequently profess that if the earth was inhabited by econs, choices wouldn’t be confusing, foolish or ignored.

Human: The authors come back to reality, saying that the world is full of humans and that humans are irrational, emotional and when overwhelmed, they tend to be lazy and intuitive, not always making good choices for themselves and looking for random cues to justify their choices.

Libertarian paternalism: is a term used by the authors to describe a ruling / governing paradigm that is a middle ground between enforcement and freedom that leads to impunity. Nothing should be enforced, but just so that people should make choices that will benefit them and for people to stay out of harm’s way, choices should be built such that the good ones are easier to choose and the bad ones are harder. This is done by monitoring and subtly arranging choices such that people automatically lean towards one rather than another. So it is like a father who gives the child freedom, but watches and subtly controls outcome.

Nudge: is a trigger in a system that gently coaxes an individual to do the following.

- If the individual has been performing ONE action out of habit, then a nudge can gently remind him / her that this is not a uni-directional road and that there are choices available and decisions to be made. E.g. a compulsive smoker or drinker can be reminded that he / she can quit smoking and lead a sober life.

- If there are too many choices, then an individual may stall making a decision or select randomly or intuitively, not making an informed decision. A nudge can direct the individual by eliminating unnecessary choices and narrowing down the options.

- Rarely, but not never, a nudge can subtly manipulate an individual and lead him / her towards a choice that is intended by the one who nudges. This is used by big brand marketers to sway consumers towards them and is not considered ethical.

Choice architecture: is a person who fully understands the situation in which an individual is required to make a choice. Thus the architect designs choices such that it becomes easy for the individuals to make a choice. Choice architects often mean well and want the choice-maker to make an informed decision rather than a random one. However, as mentioned before, certain choice architects turn to manipulation to lead people to certain choices which is not in the choice-maker’s best interest, but rather beneficial for the architect.

The invisible hand: is the counter-balancing system that puts manipulative choice architects in their place. The invisible hand usually lets people know that they have been manipulated. People will avoid that choice structure in future and bring the architect to book. In the world of business, the invisible hand is often the market and its system of reviews, whether online or word-of-mouth. Manipulative businesses have short-term gains, but often lose their market share drastically or go out of business.

When do we need a nudge?

The authors outline the following situations where choice-makers need a nudge to make the right decisions.

The authors outline the following situations where choice-makers need a nudge to make the right decisions.

- People are bad at making decisions when

- We need to bear the costs now, but the benefits much later: E.g. exercising now and gaining muscle only after a month.

- We can feel pleasure right now, but the ill effects later: E.g. binging on pastries now and gaining weight later.

- We are bad at making choices when the learning curve is steep. E.g. it is easy to decide how to cook healthy for dinner, but not how to invest for retirement.

- People will stall a decision when the losses are high and the number of attempts available are few. E.g. it is easy to decide what to build with lego blocks, but it is not easy to decide how you would like your own house built. A wrong decision can cost a lot of money and you don’t have too many attempts left until you run out of funds or time.

- If an activity does not have immediate and vivid feedback, then it is hard to make decisions. It is easy to choose one flavour of ice-cream over another, because the taste is immediate. However, it is hard to know if one car is better than in the long run, because fuel and running costs are known only when the car is used.

- If the outcome of something is uncertain or unknown, people are petrified of making a choice. Most likely, no one would volunteer to fly over the Bermuda triangle, since the outcome is uncertain.

- If a certain system is known to be manipulative, people avoid making choices. E.g. most home loans have hidden charges and fussily understood clauses. People are afraid of picking a loan and signing on the dotted line. Far too often, people walk away from what could have been their dream.

In all the above situations, a choice architect can step in and nudge people to make decisions.

Golden rules of choice architecture

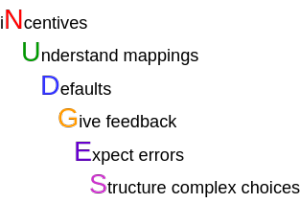

The word NUDGES forms an acronym for 6 points which are the golden rules for choice architecture.

iNcentives: Incentives can spur a person to make choices as soon as possible. Incentives should be immediate and salient. While designing incentives, a choice architect should keep the following questions in mind.

Who uses? Who chooses? Who pay? Who benefits?

Understand mappings: The mapping between a decision and its outcome should be made clear. This is especially true when choosing vendors for services such as Internet or mobile service. Often the different costs of a typical usage are not understood.

The authors suggest a system called RECAP: Record usage, Evaluate, Compare Alternative Prices. All services should be required to hand out RECAP charts for different types of usage of their systems. E.g. a phone company should consider local calls, international calls, rates for incoming calls when a user is roaming and such typical usage.

Defaults: If a choice-maker decides to pass or defer making a choice, then a good default choice should be made on his / her behalf. The default choice should be the safest choice of all. E.g. if an investor is unsure of whether his / her money should be invested in bonds, stocks or hedge funds, then given the volatility of the various choices, the default choice should be bonds. It is also possible to tell the choice-maker that no defaults are available and that a choice is mandatory. This is the default in a place like a restaurant, where the chef cannot know a person’s likes and dislikes beforehand and hence cannot make a reasonable default choice on behalf of the diner. So, unless the diner orders, he/she won’t get any food!

Give feedback: There should be some feedback as soon as possible when a choice is made. One or more of the five senses: sight, hearing, touch, smell, taste should be involved in the feedback. Otherwise it is not easy for the choice-maker to know what the possible outcome is. Even if the real feedback is a long-time coming, some kind of nudging feedback should be immediate. E.g. if an investor opts to invest in stock, then the system should warn that the choice is subject to volatility.

However, please note that warnings should be used sparingly. Warnings are subject to false positives. Too many warnings will induce a sense of immunity and future warnings will be ignored.

Expect errors: Without full knowledge, people are expected to make errors in decision. The cost of errors should be none or minimal. E.g. plenty of companies offer full refunds if the customer doesn’t think that a product isn’t for them. The cost of a misjudgement about the product is absorbed by the company, rather than by the customer.

Structure complex choices: Rather than throwing a kitchen-sink of choices on a choice-maker in the form of a list, choices should be structured such that irrelevant choices are eliminated as early as possible and the options are narrowed down. This can be in the form of questionnaires or flowcharts. A perfect way is to use a geometric shape or alignment that matches the situation. Airlines have understood this really well. They present the shape of the fuselage and the seating arrangement of the aeroplane, making it easy for the user to identify window, middle and aisle seats. This would have been difficult if simply a list of seat numbers were to be shown to the user.

What’s more?

In the rest of the book, Thaler and Sunstein illustrate case studies and examples about how humans make irrational choices and how different measures can be or have been taken to nudge choice-makers. They explore the world of personal finance, marriage, alcholism and several other topics.

Conclusion

In every walk of life, choices and decisions are inevitable. Understanding how choices work can help you make better decisions. But more so, it can help you design choices such that people can make good decisions for themselves. They will thank you for it.

We know you love books. We would you like to give two FREE audio books. Grab your trial Audible Membership with Two Free Audio Books . Cancel at anytime and retain your books.