|

Title: Ikigai |

| Author: Hector Garcia and Francesc Miralles | |

| Publisher: Random House, UK | |

| ISBN-10: 178633089X | |

| ISBN-13: 978-1786330895 | |

| Buy from: Amazon.in | Amazon.com |

Hector Garcia works as a computer software engineer for a voice recognition software company in Tokyo. Francesc Miralles, an author and publisher, has worked as a translator. As with Japanophiles around the world, the Spanish duo is obsessed with the Japanese ways of life. The two are most fascinated with Ikigai, a feeling of happiness and satisfaction with one’s life. Ikigai is a factor vital to Japanese’s happiness in day-to-day life and their longevity. A mutual friend brought the two together in Tokyo. Together they have written about their fascination for Japan and how to develop Ikigai in your own life. Here is the summary of the book.

What is Ikigai?

Roughly translated to English, Ikigai can be worded as “a feeling that makes your life happy and worth living”. Parallels have been drawn to the French term ‘raison d’être’ (pronunciation matches “rays on detr”), which literally translates to ‘reason to be’ or figuratively to ‘reason for living’. Another equivalent the authors pull up is Dr Viktor Frankl’s logotherapy, a treatment that cures people of major depression by helping them find a purpose for their lives. But the authors do warn that both the terms only roughly match Ikigai and not principle-for-principle.

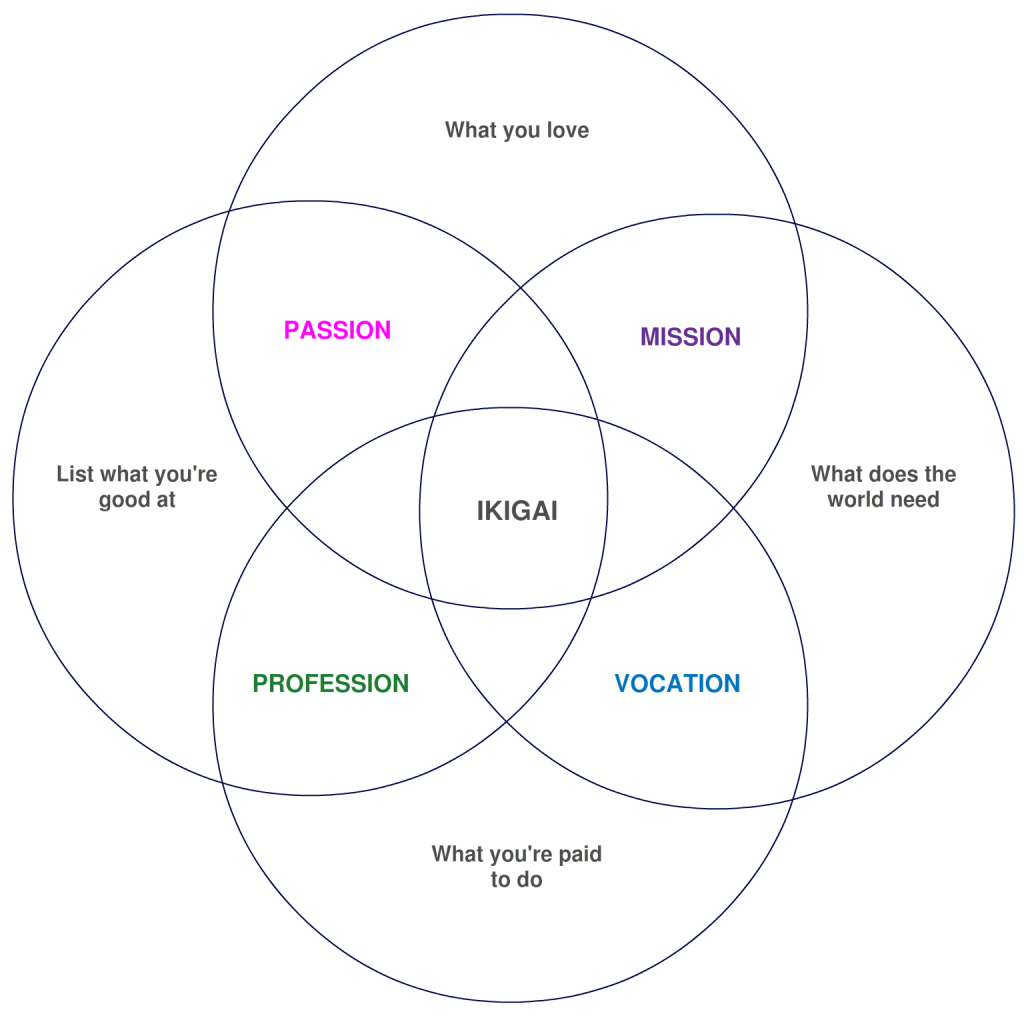

This is how the western world falsely represents Ikigai in books, magazines and blog posts.

This diagram is not true at all. It is a misrepresented adaption to conform Ikigai to the western world’s cultural and social norms. The original Japanese meaning is lost beyond recognition in the diagram!

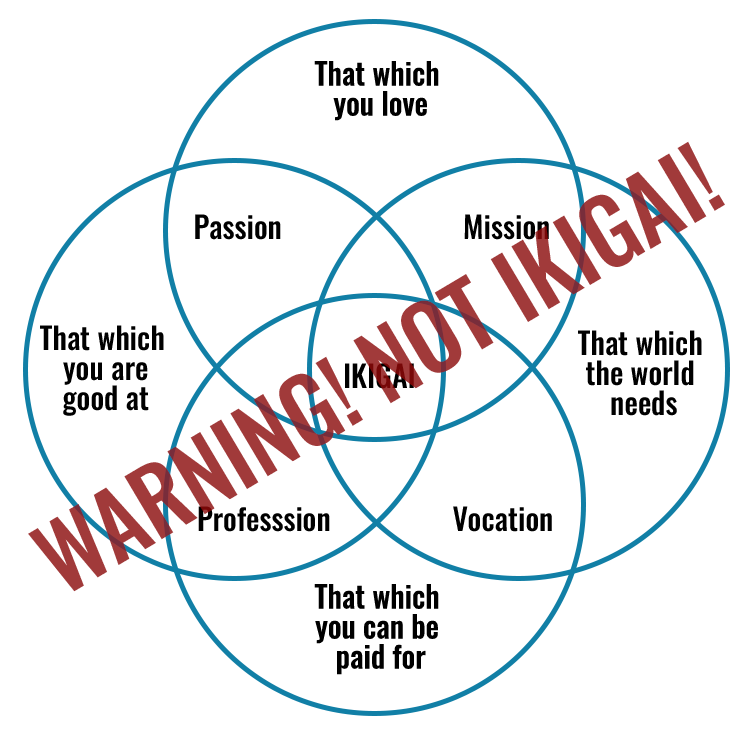

Despite using the above diagram on the first page of the book, the authors have done justice to Ikigai in the rest of the book. After reading the entire book, I agree with the diagram below.

While the comparison with raison d’être and logotherapy raises a few similarities, neither term accurately defines Ikigai. As mentioned by the authors, the two western terms mention a purpose in life. If your existence is without purpose, which is often bigger than yourself, then the two terms fall short.

Ikigai has nothing to do with finding a higher purpose. It is all about happiness. Ikigai applies even if all you want to do is chew tobacco while sitting on an easy chair or manage your WWF cards collection. As long as you really, really enjoy the activity. So much so that you look forward to doing it every day for the rest of your life, and that it is a major reason for you to continue living for several years to come. It doesn’t need to solve a higher purpose. It doesn’t need to be useful to the world or society. That’s why the circle that says, ‘that which the world needs‘ is inaccurate. Your activity needs to be meaningful to you alone. The term ‘joie de vivre’ (joy of life in French) is more representative of Ikigai.

The fourth circle that represents monetary compensation for your passion is the most inaccurate representation of Ikigai, which has nothing to do with making money or getting anything in exchange for doing that which makes you happy. Getting to do that activity is the motivation and the reward. No payouts required. Money and status are simply side-effects of a job thoroughly enjoyed and hence done well. Done so well that the world clamours to pay for it.

The authors write that the feeling of Ikigai is why Japanese, especially the ones in the island of Okinawa, are able to live much longer than the typical 100 years that is considered a human life span. There are more than 20 centenarians for every 100,000 persons on Okinawa island. Ikigai may be one of the reasons, other than healthy habits and daily activity, that spurs the centenarians to live on and on. They look forward to their next day with anticipation, excitement and positivity.

The authors’ experience

The authors travelled to several places to discover the secret of Japanese longevity. But their best moments came from their travel to Ogimi, a town within Okinawa island. The town has the highest concentration of centenarians and the highest average population age in the world. Here the duo learnt a lot from the relaxed, but active village life.

Hara Hachi Bu

This Japanese term refers to the practice of eating only until you are no hungry. Eating until you feel that your stomach can take no more is not a good idea. After pushing away your finished plate, you should feel that there is still a little breathing space in your stomach. That’s not to say that you should stay hungry and that your stomach should still rumble with emptiness. The term translates to ‘80% full’, a term later matched by Brian Wansink in his book Mindless Eating.

Hara Hachi Bu keeps the digestive system working smoothly without overloading it. It prevents partial digestion and hence stop the buildup of toxins that lead to lethargy and body decay.

The core of Hara Hachi Bu is the usage of small plates, which are tiny compared to those in the USA or Europe. The idea is to pause and consider if you are still hungry after you have eaten a tiny plateful. You are always welcome for a second or third serving, but only after you have considered if you are still hungry.

Moai: Community living

The members of the village, regardless of their age group, participate in community-wide activities. This may be in the form of festivals, dances, community sports, games or cultural programmes. The Japanese believe that everyone is connected and that everything in nature is connected. Spending time outdoors and bonding with other people strengthens those connections and revitalises your life energy.

Constant activity

Despite being octogenarians or centenarians, the Ogimi natives perform some activity that requires them to move. They aren’t lifting weights at the gym or running in tight spandex clothes. But they are constantly moving all day and not spending sedentary time. Some weave, some tend to their gardens, some shop at the marketplace and so on.

This convinced the authors that even a little bit of exercise and movement every day, and not necessarily heavy workout, can keep your body active and youthful for years.

Low stress

Because Okinawans keep their life simple and only indulge in activities they like, their stress levels are practically zero. They do not have anywhere to run, no strict schedules to keep, no bosses to please or no clients to pander to. Their simple village life gives them plenty of time with no hurry to get things done.

Because they need very simple things in life, they are okay with tiny or no profits from what they do. They make just enough to keep them comfortable. All they want is their food, the activity that brings them joy and plenty of time with their loved ones.

Working in a flow

While true of Okinawa, this principle applies to the whole of Japan. The Japanese attain a flow-like state while working. They achieve high levels of concentration and are less distracted. Since they feel joy in their work and that work is meaningful to them, it energises them. They prefer continuing to work in a deep state of focus, taking far fewer breaks for coffee or around the water cooler. They achieve more quality and are most satisfied with their work.

Treating work like a masterpiece

For the Japanese, every work is art. They do everything to the best of their abilities. They respect work and don’t like to cut corners. They also take a lot of pride in their work. It doesn’t matter if the professional is a ceramic utensil maker, a sushi maker or a fisherman. The Japanese are committed to make the best ceramic utensils, the best sushi or catch the best fish.

The authors talk about a woman who attaches bristles by hand to make-up brushes. She was happy, even excited when the authors asked to watch her work. She discussed every tiny detail of cosmetic brush making as she worked. Her boss, equally passionate about his company’s products, was forthright in letting the authors and the woman know that she was a very valuable part of the company. How many instances do we know of in India or in the western world where a company’s owner personally visits a woman who attaches bristles to makeup brushes and commends her in front of others?

An inscription from Ogimi

Outside Ogimi village is a small poem in Japanese engraved on a stone pedestal on which the local deity, bunagaya or the holy spirit, stands. The engraving from 1993 is credited to the Ogimi Senior Citizen’s Federation. The poem translates to:

At 80 I am still a child.

When I see you at 90, send me away to wait till I’m 100.The older, the stronger.

Let us not depend on our children as we age.If you seek long life and health,

welcome to our village, where you will be blessed by nature

and together we will discover the secret to longevity.

Conclusion

Japanese culture is fascinating to everyone. But of special interest is their longevity, their ability to find joy, satisfaction and pride in their work and their practice of treating every work as a masterpiece. The Spanish authors of the book have explained to us an outsider’s view of Japan and why it is vital to create Ikigai in our lives.

We know you love books. We would you like to give two FREE audio books. Grab your trial Audible Membership with Two Free Audio Books . Cancel at anytime and retain your books.